- Details

- Written by: Stuart Kenny

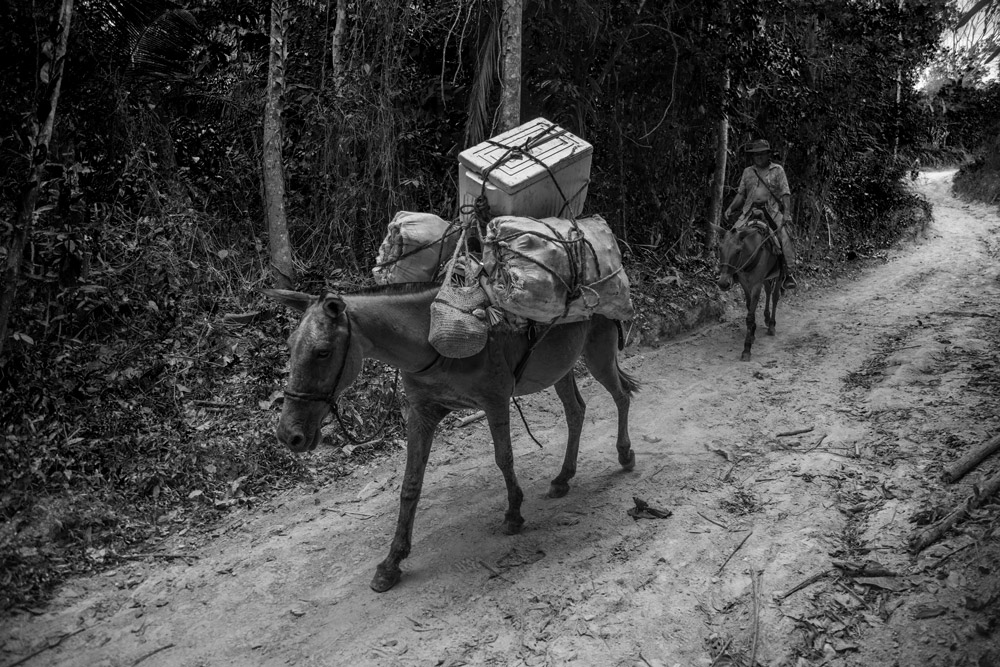

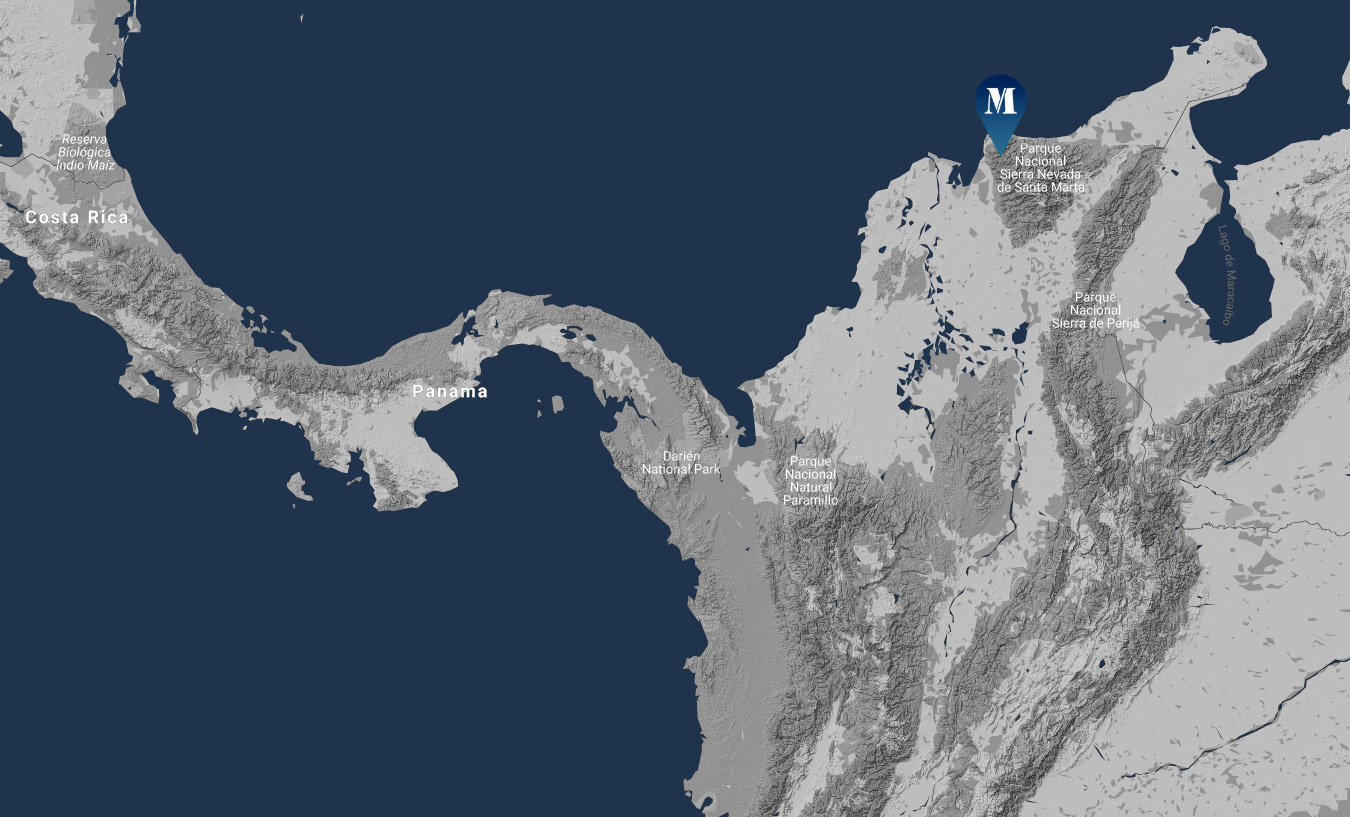

I am waist deep in a river in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta jungle; the fifth member of a ramshackle team attempting to pull two struggling mules across an overflowing river.

The mules are carrying bin bags, within which sit our last few dry possessions on the continent of South America. We’re just as concerned with the mules safety as the mules are. The animals would normally need no assistance crossing the river, but after a torrential downpour foretold by our indigenous guide Jose (he knew by looking at the pattern of ants on the jungle floor), the waters have risen and the mules are in quite the spot of bother.“This is why they want their land back… To bring the life back, where marijuana farmers and cocaine plantations have taken it away”There are few problems Jose has not seen before though, and getting a couple of mules across an overflowing river in the rainforest, during rainy season, is not one of them. Jose bounds from one riverside boulder to the next, tying ropes around trees before heading into the water himself to tie the rope onto the mules’ harnesses, while three budding hikers, including myself, and a fast-talking Colombian guide from another tour operator, prepare to do… well, something or other to help the mules get safely to the other side. Mule one begins happily enough. Then the rapids hit. The mule slows down. His eyes widen, like he’s just noticed the setting on the treadmill is too high and he doesn’t know how to turn it down.

“Everything in nature is part of our spirit. When we cut nature we cut our own spirit”The Wiwa tribe also run Wiwa Tourism, which is one of the world’s first adventure tourism companies founded by an indigenous tribe, and who, in partnership with G-Adventures, a leading sustainable travel company, have organised our five day trek to the Lost City. Jose leads the way. Along with him is Javier, another indigenous guide from the local Kogi tribe, and completing our guide team is Juan Diego, a Colombian guide from G-Adventures, who translates Jose and Javier’s Spanish throughout the tour and who is an ever-present source of optimism and encouragement.

***

The immediate elephant in the room when tourism meets an indigenous people is the concern over exploitation, of course. The first mainland Colombians to discover Teyuna were graverobbers in 1973, heading into la Sierra Nevada to try and find gold. Shockingly, what they were doing was actually legal. The government eventually intervened, but for a long time, if the military or police saw a graverobber heading up the mountains, we’re told, they’d just laugh and say “remember us when you get rich.”“This is a football pitch. Thousands of metres high in the Sierra Nevada mountains, far from the 22ft bronze statue of Carlos Valderrama”After golden relics began to turn up on the black market following the diggers discovery of the site, archaeologists finally went up in 1976 and reconstructed Teyuna. Tourism began in 1982. The Colombian government have a troubling history with their indigenous people, as do many states with their native residents. Before 1991, the indigenous tribes weren’t recognised as part of the Colombian State. To be Colombian, at that point in time, was to be Catholic. And so the indigenous were treated as savages.

***

I would perhaps have been more reluctant to clamber into the water and help those mules had it not been for the torrential downpour on day one that had left us soaked through. Juan Diego’s prediction that we would be “breathing vapours” in the mountains had proved correct. We had sweated on exposed uphill, under baking heat, for about two hours. Then by the time the rain had come we were in the jungle, and it came hard. A downhill essentially made from solidified mud became a waterslide of a descent.“There are some tourists and guides who think these people are zoo attractions”I slipped first. My makeshift jungle walking stick snapping on impact but saving my fall. Then the rest went down. Jon hit the deck, engulfing himself in reddish clay. Laura took her time, but was brought down by Tom, whizzing down on his backside, while the well-meaning Juan Diego puzzled over who to try and help first like a slapstick comedy sketch. We learned that when it rains in the rainforest, it rains suddenly and relentlessly. Following Javier’s footsteps on day one of the downpour felt like trying to trace the dance moves of a trained ballerina. He skipped across wet slabs and stones while we skidded behind, like newborn ducklings precariously but loyally following their mama duck without question. We wrung our stuff out when we got to the Wiwa Camp, but nothing dries in the humid night. Wading across an overflowing river had been the final hurdle of the day, and hadn’t helped. Still, that’s where the sun comes in handy the morning after. A good night’s sleep on a surprisingly decent bunk bed, clothes on backpack, wet boots on and off we go.

***

“Kidnapping, taking away your money, extortion. 15 years ago… this was normal”What’s the problem with the way other companies work, I ask. “These companies come here and they misinform the travellers,” Juan Diego says, who previously worked for other tour operators in the area before leaving to join G-Adventures. “I had to translate for local guides and they would all tell a different story. Their own lies.

***

“We all have the same blood”The morning comes for the final climb to Ciudad Perdida. We find ourselves at the bottom of 1200 stone steps to the top of Teyuna about six in the morning. Blink and you’d miss them. They weave and wind, and you have to take care not to slip, but when you do arrive at the top, you arrive at a truly humbling site. Javier gets there first, and welcomes us in. Surrounded by trees on every side, Teyuna is formed by various platforms of ringed stone circles. Behind these, a staircase leads up to an even higher level, where the platforms continue to rise, but with views looking out over stunning, remote forest-covered mountains.

***

“The government… used helicopters to fumigate the coca and marijuana plantations, killing many civilians who lost their farms”Edwin points to the helicopter. “After this kidnapping, as one of the requirements from the paramilitary, in order for them to turn themselves in and give up their weapons, they demanded security from the state. So after the kidnapping we raised awareness of how important this place was and the government built a high mountain battalion, and they have convoys all around the Sierra, taking care of this beautiful place, of the ancient heritage, and taking care of us.”

***

Javier and Jose tell us there are many temples like Teyuna in the jungles of the Sierra Nevada that their people will never reveal to the public. The government have asked them. But there are also many, they say, that not even they know about, that only the mamos are aware of, and if you follow a mamo without permission, we are told, you will become ill. The indigenous people did not come to their initial decision regarding tourism lightly. Several mamos went up to Teyuna and held a spiritual ceremony to consult the spirits on tourism in 1982. Even as recently as 2015, mamos reconvened and used yatkua for almost a week to consider whether or not they should work with G Adventures and Planeterra. I ask Jose, simply, if he is happy to have tourists here. “We all have the same blood,” he says. “We are all brothers. Earth has plans, and if you came here, you are here to listen to your mother. When you hear our message, and you see our nature, and you spread our message, you are doing what your mother has asked.”

“We hope to make money to recover our ancestral territory and grow as a community”“This is the first time that we’re opening [this] community to travellers, because we saw the opportunity,” says Lorenzo. “We hope to make money to recover our ancestral territory and grow as a community. “Through tourism we are seeing an opportunity to not only recover the land but the forests. We are buying back lands taken over by farmers that came here to grow illegal things. Our main aim is to recover these lands, to recover the nature and make nature reborn again.” Lorenzo is remarkably savvy. He wears the traditional white of the tribe, but with Nike trainers. He seems smart, switched on and confident in the future of his community. We are encouraged to buy handicrafts from the local women, to purchase coffee, bowls and bags before we drive back to Santa Marta, from where we’ll fly to Bogota the next day, and then on home, safe in the knowledge that the guardians of the heart of the world will continue their mission to preserve la Sierra Nevada, and indeed, their own way of life.

Do It Yourself

G Adventures’ seven-day Colombia-Lost City Trekking tour starts from £499 per person, excluding flights. 6 nights accommodation, 6 breakfasts, 5 lunches and 4 dinners are included along with a G Adventures Chief Experience Officer and Indigenous guide.

Visit www.gadventures.co.uk for more information.

G Adventures’ seven-day Colombia-Lost City Trekking tour starts from £499 per person, excluding flights. 6 nights accommodation, 6 breakfasts, 5 lunches and 4 dinners are included along with a G Adventures Chief Experience Officer and Indigenous guide.

Visit www.gadventures.co.uk for more information.